You hear it. You read it. Executive functioning, which is almost always broken in ADHD or autism and other developmental disorders and learning disabilities. Ever wonder what is executive functioning? What is executive functioning?

Image courtesy of Psychology Today. Executive Function in the brain.

Executive function (EF) (also known as cognitive control and supervisory attentional system) is an umbrella term for the management (regulation, control) of cognitive processes[1][2], including working memory, reasoning, task flexibility, and problem solving[1][3], as well as planning and execution.[1][4]

Executive function consists of several mental skills that help the brain organize and act on information. These skills enable people to plan, organize, remember things, prioritize, pay attention and get started on tasks. They also help people use information and experiences from the past to solve current problems.[5]

In short, executive function is comparable to a company’s CEO, a celebrity’s manager, a sport team’s coach, the film’s director, an orchestra’s conductor, or a computer’s CPU; all of them direct what a group or a person will do to make a group run smoothly.

Image courtesy of Balboa School. The brain’s executive function is comparable to a computer’s CPU.

There are 8 key executive functions in the brain according to Understood.[6] What are they?

Eight Key Executive Functions:

- Impulse Control – helps your child think before acting.

- Emotional Control – helps you child keep his feelings in check.

- Flexible Thinking – allows your child to adjust to the unexpected.

- Working Memory -helps your child keep key information in mind.

- Self-Monitoring – allows your child to evaluate how you’re doing.

- Planning and Prioritizing – help your child decide on a goal and a plan to meet it.

- Task Initiation – helps your child take action and get started.

- Organization – lets your child keep track of things physically and mentally.

Two of the major ADHD researchers involved in studying EF are Russell Barkley, PhD, and Tom Brown, PhD, have also their own version of key executive functions[7]:

Barkley breaks executive functions down into four areas[7][8]:

- Nonverbal working memory

- Internalization of Speech (verbal working memory)

- Self-regulation of affect/motivation/arousal

- Reconstitution (planning and generativity)

Brown breaks executive functions down into six different “clusters.”[7][9]

- Organizing, prioritizing and activating for tasks

- Focusing, sustaining and shifting attention to task

- Regulating alertness, sustaining effort and processing speed

- Managing frustration and modulating emotions

- Utilizing working memory and accessing recall

- Monitoring and self-regulating action

Hmm.. they’re like the soccer team. Each member must function and cooperate well to win a game.

(C) Cartoon Network. Key executive functions are like a soccer team.

With executive function in sync, learning is much easier for a growing child up to his adulthood.

How executive function develops?

A range of tests measuring different forms of executive function skills indicate that they begin to develop shortly after birth, with ages 3 to 5 providing an important window of opportunity for dramatic growth in these skills. Growth continues throughout adolescence and early adulthood; proficiency begins to decline later in life.[10]

Image courtesy of Harvard University/NIH Toolbox project. This graph shows executive function development and proficiency across the life span.

Where in the brain is executive function?

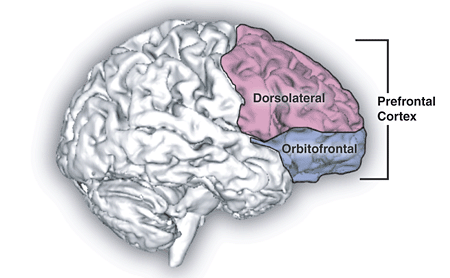

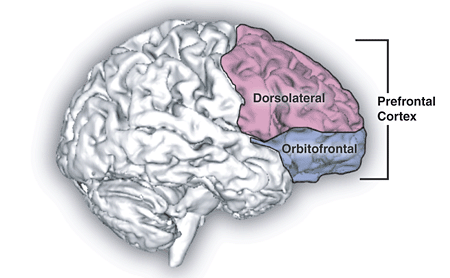

Historically, the executive functions have been seen as regulated by the prefrontal regions of the frontal lobes,[1] but a review found indications for the sensitivity but not for the specificity of executive function measures to frontal lobe functioning. This means that both frontal and non-frontal brain regions are necessary for intact executive functions.[1]

Neuroimaging and lesion studies have identified the functions which are most often associated with the particular regions of the prefrontal cortex.[1][11]

The prefrontal cortex has its parts where specific executive functions are:

- The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is involved with “on-line” processing of information such as integrating different dimensions of cognition and behaviour.[12] As such, this area has been found to be associated with verbal and design fluency, ability to maintain and shift set (mental ability to switch between thinking about two different concepts, and to think about multiple concepts simultaneously), planning, response inhibition, working memory, organisational skills, reasoning, problem solving and abstract thinking.[11][13]

- The anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) is involved in emotional drives, experience and integration.[12] Associated cognitive functions include inhibition of inappropriate responses, decision making and motivated behaviours. Lesions in this area can lead to low drive states such as apathy (absence of feelings), abulia (lack of will or initiative) or akinetic mutism (patients tending neither to move (akinesia) nor speak (mutism)) and may also result in low drive states for such basic needs as food or drink and possibly decreased interest in social or vocational activities and sex.[12][14]

- The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) plays a key role in impulse control, maintenance of set, monitoring ongoing behaviour and socially appropriate behaviours.[12] The orbitofrontal cortex also has roles in representing the value of rewards based on sensory stimuli and evaluating subjective emotional experiences.[15] Lesions can cause disinhibition, impulsivity, aggressive outbursts, sexual promiscuity and antisocial behaviour.[11]

Image courtesy of Wikipedia/Natalie M. Zahr, Ph.D., and Edith V. Sullivan, Ph.D. Preforntal cortex in the brain’s frontal lobe.

When children have opportunities to develop executive function and self-regulation skills, individuals and society experience lifelong benefits. These skills are crucial for learning and development. They also enable positive behavior and allow us to make healthy choices for ourselves and our families.[10]

When children have opportunities to develop executive function and self-regulation skills, individuals and society experience lifelong benefits.

We usually have this executive function taken for granted. But for people in neurodiversity, their executive function is broken or impaired, inhibiting their normal functioning.

What happens if executive function is impaired?

If executive functioning is working well and the task is fairly simple, the brain may go through these steps in a matter of seconds. If your child has weak executive skills, though, performing even a simple task can be challenging. Remembering a specific word may be as big a struggle as planning tomorrow’s schedule.[5]

When executive functioning is impaired, all of its functions cannot be done or sustained. Hence, this is called executive function disorder (EFD) or executive dysfunction.

If your child has executive functioning issues, any task requiring these skills could be a challenge. That could include doing a load of laundry or completing a school project. Having issues with executive functioning makes it difficult to:

- Keep track of time

- Make plans

- Make sure work is finished on time

- Multitask

- Apply previously learned information to solve problems

- Analyze ideas

- Look for help or more information when it is needed[5]

To explain this further, let’s include the 8 key executive functions and how they become impaired when executive function is broken:

- Impulse Control – Kids with weak impulse control might blurt out inappropriate things. They’re more also likely to engage in risky behavior.[6]

- Emotional Control – Kids with weak emotional control often overreact. They can have trouble dealing with criticism and regrouping when something goes wrong.[6]

- Flexible Thinking – Kids with “rigid” thinking don’t roll with the punches. They might get frustrated if asked about something from a different angle.[6]

- Working Memory – Kids with weak working memory have trouble remembering directions – even if they’ve taken notes or you’ve repeated them several times.[6]

- Self-Monitoring -Kids with weak self-monitoring may be surprised by a bad grade or negative feedback.[6]

- Planning and Prioritizing – Kids with weak planning and prioritizing skills may not know which parts of a project are most important.[6]

- Task Initiation – Kids who have weak task initiation skills may freeze up because they have no idea where to begin.[6]

- Organization -Kids with weak organization skills can lose their train of thought – as well as their cell phone or homework.[6]

EFD is relatively common in neurodiversity and less so in neurotypical people and can affect people of any degree of intelligence and capability.[16] Unfortunately, EFD is often mistaken as ADHD or LD (learning disabilities) by doctors (ADHD can have no EFD, just their hyperactive and inattentive problems). But despite giving learning therapies, children with EFD do not respond to them, thus mistaking them as lazy, unmotivated, stubborn or uncooperative. Usually, nothing could be further from the truth. They are working as hard as they can to keep pace with the demands in their lives.[16]

Very bad. Not only they will suffer in school and cause educational underachievement – suspension, dropping out of school, repeating a grade, but also they will have a high risk of becoming unemployed and socially isolated, increasing risk for mental disorders.

What causes EFD?

In most cases of executive dysfunction, deficits are attributed to either frontal lobe damage or dysfunction, or to disruption in fronto-subcortical connectivity. Neuroimaging with PET and fMRI has confirmed the relationship between executive function and functional frontal pathology.[2][17] Certain genes have been identified with a clear correlation to executive dysfunction and related psychopathologies.[17] Not surprisingly, plaques and tangles in the frontal cortex can cause disruption in functions as well as damage to the connections between prefrontal cortex and the hippocampus.[17][18] Another important point is in the finding that structural MRI images link the severity of white matter lesions to deficits in cognition.[17][19]

The heritability of executive functions is among the highest of any psychological trait.[17][20] The dopamine receptor D4 gene (DRD4) with 7′-repeating polymorphism (7R) has been repeatedly shown to correlate strongly with impulsive response style on psychological tests of executive dysfunction.[17][21]

Image courtesy of The Telegraph. This is a messy table. Can be an EFD or just simply lazy.

What needs to be done for EFD?

Early assessment needs to be done to avoid problems in school, work, and social relationships that could affect a person with EFD.

According to a local expert on EFD, Sarah Ward, M.S.,CCCSLP, of Lincoln, Massachusetts, one of the biggest complaints about children with EFD is, “They did it yesterday, why can’t they do it today?” For such children, however, the organizing pattern is not established in one pass; pathways must be developed through repeated practice. An important method of helping these kids is by teaching processing skills. Ward believes that this can be done most effectively through[16]:

- Segmentation: Teaching (not telling) students how to break down a task into smaller, manageable parts.

- Verbal approach: Using declarative language, instead of imperative language

- Mental picturing: Teaching students to think through a situation in order to envision how a goal can be accomplished

- Using visuals as a reinforcement.

Now, there is an application of these strategies in the following quotation from aane.org[16]:

Ward gives an example that uses these four techniques. A child was asked to set the table for dinner. She got stuck and overwhelmed in her attempts to do the task.

- The child was helped to break down the task to a manageable level, in this case putting out four plates.

- Once this was accomplished, the use of declarative language helped determine the next step. Rather than saying, “Okay, now put out the forks and knives” (imperative), the statement Ward made was, “Great, the plates are out. Now we’ll need something to eat the food with” (declarative).

- In this one brief statement, the child was given specific positive feedback for what she had done (“Great, the plates are out” as opposed to the generic “Good job”), and was asked to assess the situation and figure out what came next.

- Ward often uses photos or drawings to reinforce the concept being taught. In this case she used a photo of a correctly set table. It “conjured up the whole” and showed what it would look like if the table were set properly. Ward often uses stock images such as those found in Google Images (Ward even Googled Hamlet to show whatever images there were to help a student write an essay about the character!)

These concepts work equally well in school situations. As teachers we often say something like, “Take out your ruler and calculator and get ready for math.” Ward suggests that a better way to help students develop skills that will generalize to future situations is to say, “We’re going to do graphing now. How would your desk look? What is involved in graphing?” This teaches the student to become more self-directed by encouraging the development of self-talk, which Ward calls “notes to self.” The development of this kind of self monitoring is essential to effective, independent thinking and functioning.

Another crucial concept children need to learn, Ward says, is the “sweep and passage of time.” She explains that we teach kids to read the clock, but this has little to do with monitoring the passage of time. Ward uses a wall clock with a glass cover and actually draws on its surface with erasable markers to block off the amount of time that will be allowed for a task. In Ward’s estimation this concrete visual “pie shape” method of demonstrating the passage of time gives a sense of control and improves motivation, because “They can see they are succeeding.”

There are tests to diagnose EFD in people. Here they are:

Clock Drawing Test (CDT) – The Clock drawing test (CDT) is a brief cognitive task that can be used by physicians who suspect neurological dysfunction based on history and physical examination.[17]

The procedure of the CDT begins with the instruction to the participant to draw a clock reading a specific time (generally 11:10). After the task is complete, the test administrator draws a clock with the hands set at the same specific time. Then the patient is asked to copy the image.[17][22] Errors in clock drawing are classified according to the following categories: omissions, perseverations, rotations, misplacements, distortions, substitutions and additions.[17][23] Memory, concentration, initiation, energy, mental clarity and indecision are all measures that are scored during this activity.[17][24] Those with deficits in executive functioning will often make errors on the first clock but not the second.[17][23]

Stroop task – The Stroop task requires the participant to engage in and allows assessment of processes such as attention management, speed and accuracy of reading words and colours and of inhibition of competing stimuli.[17][25] The stimulus is a colour word that is printed in a different colour than what the written word reads. For example, the word “red” is written in a blue font. One must verbally classify the colour that the word is displayed/printed in, while ignoring the information provided by the written word. In the aforementioned example, this would require the participant to say “blue” when presented with the stimulus. Although the majority of people will show some slowing when given incompatible text versus font colour, this is more severe in individuals with deficits in inhibition. The Stroop task takes advantage of the fact that most humans are so proficient at reading colour words that it is extremely difficult to ignore this information, and instead acknowledge, recognize and say the colour the word is printed in.[17][26]

Wisconsin card sorting test (WCST) – The WCST utilizes a deck of 128 cards that contains four stimulus cards.[17][25] The figures on the cards differ with respect to color, quantity, and shape. The participants are then given a pile of additional cards and are asked to match each one to one of the previous cards. Typically, children between ages 9 and 11 are able to show the cognitive flexibility that is needed for this test.[17][27][28]

Trail-making test – This test is composed of two main parts (Part A & Part B).[17] The participant’s objective for this test is to connect the circles in order, alternating between number and letter (e.g. 1-A-2-B) from start to finish.[17][29] The participant is required not to lift their pencil from the page. The task is also timed as a means of assessing speed of processing.[17][30] Set-switching tasks in Part B have low motor and perceptual selection demands, and therefore provide a clearer index of executive function.[17][31] Throughout this task, some of the executive function skills that are being measured include impulsivity, visual attention and motor speed.[17][30]

What about the adult with EFD?

Just like the child/student with EFD, an adult who has it certainly has problems in working memory, task completion, and emotional regulation. An adult with EFD will struggle to sustain a regular job, run a household, and control her emotions as well as maintaining relationships.

The adult with EFD experiences the following struggles in an excerpt from the Yellow Brick Program:

For those emerging adults who are not competent in these life skills, their self-image and self-esteem suffer tremendously. They feel debilitating shame and self-recrimination. They try to hide their incompetence, not asking for help, soon they are overwhelmed with dirty laundry, broken appliances, messy refrigerators, and unpaid bills. For example, one young man is fully capable of showering, dressing himself, and making it to appointments, but he has never experienced independent living. He has not learned how to do laundry, budget his money, or set up utilities in a new apartment.

He feels great shame and self-contempt, as if he’s “supposed to know how” to do these things, even though he has not had a chance to learn. Instead of reaching out to those around him who can show him the way, he denies his needs out of humiliation and self-condemnation. Instead of asking for assistance, he laughs at the thought, stating he doesn’t need the help. At these moments, he feels utterly alone in the world, unable to request the help he needs because he thinks he should already know how to do everything. Even when those around him offer support, he brushes it off, later resenting that no one is there to support him. The idea of successfully living an independent life seems hopeless.

To a parent, teacher, or boss, what looks like laziness or irresponsibility may actually be executive functioning deficits, which are neurological mechanisms tied to specific brain functions key to development at this age. The parent sees the son who isn’t showering and is distressed, concludes that he is lazy or doesn’t care about his appearance, when it is really a deficit in the executive function of “initiation.” A teacher observes a student who forgets to turn in homework all the time and concludes that student is irresponsible when, really, it is a deficit in “planning.” A boss sees an employee who gets stuck on simple tasks as “dumb” when, in reality, it is a deficit in “problem-solving.”[32]

Very embarrassing, isn’t it?

That’s why identification of a executive function disorder is important in order to manage its problems so the person affected will have less problems in his everyday life. Managing EFD in adults is similar to therapies done on children, but on an adult level.

If you are a person with EFD or suspected EFD, follow the given intervention above of segmentation of tasks to avoid confusion. Also, try to choose a job with less “procedural” tasks, i.e., musician versus nurse (where a nurse has a lot of “procedural” tasks that needs very intact executive function; musicians do not need to have that as they are only require to repeatedly play a musical instrument plus memorize a particular piece).

Remember, next time you encounter a”lazy” child or “disorganized person,” maybe you can suspect that he has impaired executive function, which most of us would normally take it for granted.

To conclude this, let’s take an excerpt from all-gifted.com:

Before that goes away, we as parents must work hard so that our children at least keep up with the work required of them. We must chip in to help, teach time management and organization skills, and look out for tools to phase them into self-reliance.[33]

That’s right. The earlier the identification and assessment, the better.

So if you have a child who is so gifted in other areas that his executive function falls behind and into judgmental eyes, would you crucify him for what he lacks, or would you patiently work and put things in place for him until he finds his next champion or develop his own planning methodologies and coping strategies?[33]

References:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_functions

- Elliott R (2003). Executive functions and their disorders. British Medical Bulletin. (65); 49–59

- Monsell S (2003). “Task switching”. TRENDS in Cognitive Sciences 7 (3): 134–140.doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00028-7. PMID 12639695.

- Chan, R. C. K., Shum, D., Toulopoulou, T. & Chen, E. Y. H., R; Shum, D; Toulopoulou, T; Chen, E (2008). “Assessment of executive functions: Review of instruments and identification of critical issues”. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology. 2 23 (2): 201–216.doi:10.1016/j.acn.2007.08.010. PMID 18096360.

- https://www.understood.org/en/learning-attention-issues/child-learning-disabilities/executive-functioning-issues/understanding-executive-functioning-issues

- https://www.understood.org/en/learning-attention-issues/child-learning-disabilities/executive-functioning-issues/key-executive-functioning-skills-explained

- http://www.help4adhd.org/faq.cfm?fid=40tid=9varLang=en

- Barkley, Russell A., Murphy, Kevin R., Fischer, Mariellen (2008). ADHD in Adults: What the Science Says (pp 171 – 175). New York, Guilford Press.

- Brown, Thomas E. (2005). Attention Deficit Disorder: The Unfocused Mind in Children and Adults (pp 20 – 58). New Haven, CT, Yale University Press Health and Wellness.

- http://developingchild.harvard.edu/key_concepts/executive_function/

- Alvarez, J. A. & Emory, E., Julie A.; Emory, Eugene (2006). “Executive function and the frontal lobes: A meta-analytic review”. Neuropsychology Review 16 (1): 17–42. doi:10.1007/s11065-006-9002-x.PMID 16794878.

- Lezak, M. D., Howieson, D. B. & Loring, D. W. (2004). Neuropsychological Assessment (4th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511121-4.

- Clark, L., Bechara, A., Damasio, H., Aitken, M. R. F., Sahakian, B. J. & Robbins, T. W., L.; Bechara, A.; Damasio, H.; Aitken, M. R. F.; Sahakian, B. J.; Robbins, T. W. (2008). “Differential effects of insular and ventromedial prefrontal cortex lesions on risky decision making”. Brain 131 (5): 1311–1322.doi:10.1093/brain/awn066. PMC 2367692.PMID 18390562.

- Allman, J. M., Hakeem, A., Erwin, J.M., Nimchinsky E. & Hof, P., John M.; Hakeem, Atiya; Erwin, Joseph M.; Nimchinsky, Esther; Hof, Patrick (2001). “The anterior cingulate cortex: the evolution of an interface between emotion and cognition”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 935 (1): 107–117.Bibcode:2001NYASA.935..107A. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03476.x. PMID 11411161.

- Rolls, E. T. & Grabenhorst, F., Edmund T.; Grabenhorst, Fabian (2008). “The orbitofrontal cortex and beyond: From affect to decision-making”.Progress in Neurobiology 86 (3): 216–244.doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.09.001. PMID 18824074.

- http://www.aane.org/asperger_resources/articles/education/executive_function_disorder.html

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Executive_dysfunction

- Clark C, Gallo J, Glosser G, Grossman M (2002). Memory encoding and retrieval in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 16(2); 190–96

- Buckner, R. (2004). Memory and executive function in aging and AD: multiple factors that cause decline and reserve factors that compensate” Neuron 44;195–208

- Friedman, et al (2008). Individual differences in executive functions are almost entirely genetic in origin. Journal of experimental psychology, 137(2), 201–10.

- Langley K, Marshall L, Bree M van den, Thomas H, Owen M, O’Donovan M, Thapar A (2004). Association of the dopamine D4 receptor gene 7-repeat allele with neuropsychological test performance of children with ADHD” American Journal of Psychiatry161(1),133–38.

- Jeste DV, Legendre SA, Rice VA, et al (2004). “The clock drawing test as a measure of executive dysfunction in elderly depressed patients.” Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology. 17(190)

- Shulman, K (2000). Clock drawing: Is it the ideal cognitive screening test? International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 15(6); 548–61

- Damasio H, Rudrauf D, Tranel D, Vianna E (2008). Does the clock drawing test have focal neuroanatomical correlates? Neuropsychology. 22(5); 553–62

- Biederam J, Faraone S, Monutaeux M, et al (2000). Neuropsychological functioning in nonreferred siblings of children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 109(2); 252–65

- MacLeod C (1991). Half a century of research on the Stroop effect: An integrative review”Psychological Bulletin 109(20); 163–203

- Kirkham, N. Z.; Cruess, L.; Diamond, A. (2003). “Helping children apply their knowledge to their behavior on a dimension-switching task”. Developmental Science 6: 449–476. doi:10.1111/1467-7687.00300.

- Chelune, G. J.; Baer, R. A. (1986). “Developmental norms for the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test”. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology 8: 219–228. doi:10.1080/01688638608401314.

- Gaudino E, Geisler M, Squires N (1995). Construct validity in the trail making test: What makes part B harder? Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 17(4); 529–35

- Conn H (1977). Trail-making and number-connection tests in the assessment of mental state in portal systemic encephalopathy. Digestive Diseases. 22(6); 541–50

- Arbuthnott K, Frank J (2000). Trail making test, Part B as a measure of executive control: validation using a set-switching paradigm. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 22(4); 518–28

- http://www.yellowbrickprogram.com/Papers_By_Yellowbrick/ExecutiveFunctionEmergingAdult_P1.html

- http://www.all-gifted.com/executive-dysfunction.html

Further Reading:

- http://www.additudemag.com/adhd/article/8392.html

- https://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/aristotles-child/201107/executive-functioning-and-the-troubled-brain

- http://www.rainbowrehab.com/executive-functioning/

You must be logged in to post a comment.